John Steinbeck (1902-1968) was, with Hemingway, Faulkner and Fitzgerald, among the small handful of American literary giants of the twentieth century; the author of such classic novels as Of Mice and Men, The Grapes of Wrath, Tortilla Flat, Cannery Row and East of Eden. His achievements were recognised with the Pulitzer Prize in 1940 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962, among many other awards. When he accepted the Nobel in Stockholm, he declared with typical eloquence: ‘The writer is delegated to declare and to celebrate man’s proven capacity for greatness of heart and spirit, for gallantry in defeat, for courage, compassion and love. In the endless war against weakness and despair, these are the bright rally flags of hope and of emulation. I hold that a writer who does not believe in the perfectibility of man has no dedication nor any membership in literature.’

There is, of course, often a dramatic, even jarring difference between the writer’s art and his life, between what the writer puts on the page and how he conducts himself in human affairs. As a man, like most men, Steinbeck had inconsistencies of character, some of them glaring. He drank too much, often to the point of inebriation; he could be thin-skinned and spiteful, hated all forms of criticism, and was (in his first two marriages) unfaithful in his relationships. These early marriages failed in part because of the way that he behaved, without much consideration for his spouses.

This self-centred behavior came naturally. Steinbeck grew up in a lovely outpost of American life, in Salinas, California, the only son of a prosperous, middle-class family; needless to say, his mother and three sisters – Elizabeth, Esther and Mary – doted on him. Spoilt from an early age, the center of family attention, his needs were met by adoring women. His father seems to have been a remote figure who paid a minor role in his development. The family circle was, for him, an entirely comfortable spot, which he sought to reproduce in his three marriages. To the end of his life, he expected that every wish would be met, and to a surprising degree this happened. He was a lucky man.

His first wife, Carol Henning, adored him. She was brilliant and, by many accounts, quite contrary and demanding herself. They met at Lake Tahoe in 1928, when Steinbeck was just beginning his career as a novelist, working on a forgettable novel about pirates! They married in 1930, and Carol stood shoulder to shoulder with her husband through his most productive years, often editing what he wrote. These were the years of his famous California stories and novels, the work for which he will be ever remembered. She was an eager sounding board and intellectual companion; indeed, she gave him the title of his best-known work, The Grapes of Wrath. But Steinbeck drank far too much, was often irascible, and he had a roving eye. In California, in 1938, he met a woman fourteen years younger: Gwen (or ‘Gwyn’) Conger. She was a singer at a club near Los Angeles, and Steinbeck fell for her at once, although he was shy by nature and it took some time for them to consummate this relationship.

Soon after Steinbeck’s divorce from Carol, in 1943, he married Gwyn, and in the six years of their marriage they had two sons, Thom and John, and moved around a great deal: it was always an awkward and unhappy connection, exacerbated by the shifting circumstances of their lives. They lived in Monterey for a time, or in New York City, often travelling to Mexico and elsewhere. Steinbeck was a restless man and he seems never to have settled into the marriage with Gwyn, whom many of his friends disliked. As it was, his beloved sister, Beth, said of Gwyn: ‘She was awful. You couldn’t trust her one bit. I sure didn’t. Nobody did, except John – and he learned the hard way about that girl.’

This latter quotation comes from an interview I did with Beth (Steinbeck) Ainsworth when I was writing my 1994 biography of Steinbeck. I had written that book at the invitation of Steinbeck’s third wife, Elaine, whom Steinbeck met in 1949 (after his divorce from Gwyn) and married in 1950. John and Elaine moved quickly for the East Coast, leaving California for good. From this point forward, they moved between an apartment in New York City and a small, beautifully situated house at Sag Harbor, on Long Island. There Steinbeck wrote his last books in an octagonal ‘summer house’ with a view of the water. Theirs was a happy marriage that lasted until Steinbeck’s death in 1968. (Elaine and I were great friends, and I often visited her in New York and once at Sag Harbor.)

To me, Elaine had no positive words for Gwyn, whom she often told me was unstable and alcoholic, an unstable mother to her sons, and someone whom John never trusted with the children. I found in writing my biography it was impossible to get a good take on Gwyn. Steinbeck had been wildly attracted to her: she was beautiful, tall and willowy. She had a lot of energy and intelligence, or so I gathered from various accounts. But as she had passed away, it was impossible to know how she felt about her famous husband and what that marriage was really like. Did Steinbeck value her? Did he treat her well? Did they have much in common? Was he a consistent husband, someone she could trust? What sort of effect did she have on his writing life, and why did the quality of his writing often seem to waver in the forties, fifties and sixties?

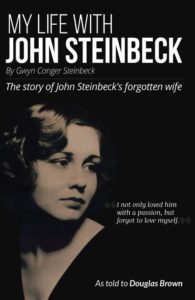

The little book before you, My Life with John Steinbeck, is a memoir of her marriage to Steinbeck by Gwyn, that has just come to light. To a degree, it answers these questions, and it’s a compelling story, with many biographical details, asides and anecdotes that make it well worth the price of admission. Published here for the first time, it’s a genuinely significant literary discovery. Her memoir sheds light on a part of Steinbeck’s life that has been in shadow for over half a century. As readers will discover, Gwyn’s voice is passionate, radiant and clear, and it tells us a lot about why Steinbeck might have fallen in love with her.

What is no longer in doubt is that she loved him deeply and regretted the course their marriage took, although this love was complicated in many ways by his rudeness, his selfishness, his lack of concern for Gwyn, who herself strikes me as a difficult character. Near the end of this memoir, she writes that ‘somewhere our love for each other was turned off, for a moment.’ But she swears that it didn’t die: ‘I know that the love we shared with each other never really ended and it never will.’

Her words might seem like a piece of sentimentality, a latent somewhat fantastic flash of fondness by a former wife who found her marriage less than tolerable. Gwyn was the one who terminated it, as she firmly reminds us here. So what went wrong? Many things, it would appear. At one point, for instance, Gwyn comments on the fact that John was ‘taking aphrodisiacs.’ She writes: ‘He would get drunk and take those pills and want to plunge into his conjugal rights and have heavy sex. It is common knowledge that a man who has had a little too much to drink will not be exactly at his best when it comes to making love. John usually tried when he was in that condition, though there were times when he was half in that condition, and even when he was just a little merry.’ She continues to say that she knew that ‘unless there were some drastic changes in John’s attitude,’ the marriage would never last, and it didn’t.

The affair began slowly enough, with notes passed back and forth between them, and casual meetings when Steinbeck would visit Los Angeles; in due course, they fell into bed. It was a rainy weekend, and they took to each other passionately.

‘I gave myself to him, willingly. It seemed like years since our first meeting. I thought of nothing but him. In bed, he was strong,’ she recalls: ‘I was ready for him, and he for me. We wanted each other, and gave ourselves to each other, passionately.’

But the relationship had its ups and downs from the outset, as John was often moody and remote, restless, irritable and demanding. In one extraordinary moment described here, he brought Gwyn and Carol together and told them to fight it out. He would go with one or the other, and he seems not to have cared which of these women succeeded in the battle over his soul. Briefly, Carol had won the day, insisting she must keep her husband. But soon that fell apart, for good, and Steinbeck married Gwyn.

Her opinion of him darkened soon after the marriage, as his daily habits often appalled her. He had a rat for a pet, for instance, and by Gwyn’s account, he was naturally cruel: ‘John was a sadistic man, of many emotions, but being sadistic was one of his private qualities.’ He would let loose his pet rat to frighten visitors, especially women. And he seems to have enjoyed doing so. (The rat seems to have represented Steinbeck’s ‘shadow self,’ to adopt a phrase from Carl Jung: he used the rat to embody a seamy and frightening aspect of himself.)

Gwyn’s story is full of harsh moments, often turning on her sense of betrayal, as when he preferred to talk to Lady ‘M’ in New York rather than her. The implication that he was having an affair with her is strong. Steinbeck often travelled by himself, and Gwyn worried that he was lost in his own world, drifting away from her, preferring the company of famous friends. As it happened, he was doing a great deal of film work in the forties, writing Lifeboat and Medal for Benny, and working on other scripts, including a documentary in Mexico. He moved among Hollywood stars, some of them close friends, such as Burgess Meredith. He drank to excess and cursed critics who dared to challenge the greatness of his work. He sought adventures away from home, as when in the middle of the Second World War he suddenly (over Gwyn’s objection) set off for North Africa and Italy as a war correspondent, nearly getting himself blown up in the Battle of Salerno. (His collection of reports from the front, Once There Was a War, remains one of my favorite Steinbeck books.)

Gwyn proves an able observer of Steinbeck, the writer. She notes his almost fanatical dedication to his work: ‘He began his same usual work schedule, the one he kept to whenever he wrote, no matter where we lived. He arose early and made his ranch coffee. He always wanted a good brand of coffee, and it was always ranch coffee. A little past daylight he began his day and after our coffee and talk sessions John, with his pyjama top and khakis went into his nest, usually by seven or seven-thirty.’ He took a brief break for lunch at noon, although he rarely said much to her during these meals, not wishing to disturb whatever was happening in his head: ‘If he was going strong he would only have more coffee. He never talked, never said a word and I would not speak to him. Usually, his average output in those days was anywhere from twenty-five hundred words to five thousand words a day.’

Gwyn felt excluded, unable to get into her husband’s field of consciousness, watching him from a remote distance. In her view, he was not a good father and took little interest in Thom or John. She had eventually to sue him in Family Court for Child Support, which Steinbeck gave only reluctantly. There was nothing good about this marriage, it would seem, and yet – if we are to believe Gwyn, and I do – she loved him dearly, and was always glad to have been married to a passionate and creative man, however impossible he might be.

She had a ringside seat to his creativity, and was there when he wrote The Moon is Down, Cannery Row, The Wayward Bus, The Pearl and other works. She saw first-hand how he managed, with deliberate effort and almost inhuman concentration, to write in the midst of chaos; some of this arose because of their unhappy marriage, which probably should never have occurred, as it didn’t do much for the couple and was undeniably harmful for the children.

This memoir should fascinate anyone who loves the work of Steinbeck, and who wants to know as much as possible about his world. What sort of man was he? How did he manage to write so much and so well? The answers that Gwen gives to so many questions are not pleasant ones, and her bitterness shows through, in these recollections. How could it not? But there is something authentic about her response to the man, John Steinbeck, whom she married, and with whom she had two sons. Authenticity shines through these pages; that cannot be denied.

Jay Parini (Biographer – John Steinbeck A Biography 1994)