Just finished re-reading The Moon is Down, Steinbeck’s novella of the reaction of a small town’s population, in northern Europe perhaps, when they are occupied by unnamed invaders – undoubtedly based on a German army, but never specifically so described. This could have been because of Steinbeck’s German ancestry.

Gwyn Conger describes her trip with John to Scandinavia, in October 1946, where many Steinbeck titles are still in print. The Steinbecks visited Denmark and Sweden where Gwyn recalled she caught pneumonia and stayed to recuperate. John had gone to Scandinavia because he knew he had royalties to spend and had also been invited to receive an award from King Haakon in Norway, for writing the novella, which had inspired Resistance fighters throughout Europe.

King Haakon VII, who had ruled since 1905, was much revered for his role in uniting Norwegians in their defiance of the Nazis during five years of occupation. He and his government had set up a government in exile in London, from where many of his speeches, providing inspiration, were broadcast via the BBC World Service to Norway.

The “Moon” title comes from Shakespeare as does that for The Winter of Discontent. Banquo in Macbeth asks his son Feance ‘How goes the night, boy?’ to which the reply is ‘The moon is down, I have not heard the clock.’ It was filmed in 1943 starring, among others, Sir Cedric Hardwicke and Lee.J.Cobb.

In Norway, Gwyn relates that John recalled the elderly King Haakon stabbing her husband with the medal pin, as he bestowed the award – recounting ‘it was the only time, the only wound for which he received a medal.’

Having left the children at home for a month-long trip, Gwyn was keen to return to them – after all John Jnr. was only one year old. John Snr. wound her up while they were away, by threatening to buy a farm in Upsala – in Sweden, but after, in Gwyn’s terms “a battle of words”, any rift between them was patched up – at least for a while.

The Moon is Down itself is intriguing with both sides, occupier and occupied, unable to break the circle of civil disobedience, reprisal and ever escalating hatred and murder. In turn, one of the occupying officers, the almost likable Anglophile, Captain Bentick, is killed by a miner Alexander Morden with a pickaxe. The unnamed town is of strategic importance because of its coalmine and port facility. Morden is then shot and his attractive widow, Mollie, later lures a lower ranking officer into her home. They are both simply lonely but she stabs him to death, with a pair of scissors, before going into hiding.

Both sides feel trapped and the book ends with both occupied and occupier melancholy about the final outcome, with the occupiers more so as they have no moral right to be there

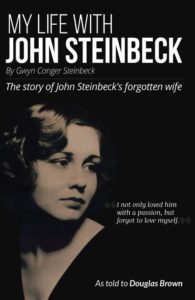

(Gwyn’s trip to Scandinavia lasted weeks in October/November 1946. They stayed in Copenhagen in Denmark and Stockholm in Sweden before John travelled on, alone, to Norway. The trip is described in Chapter 16 – A Love Dies – of My Life With John Steinbeck, available in paperback from www.spdbooks.org or as E-book from Kindle Direct.)